How The Urban School and California manage vaccination exemptions

California continues to be at the forefront of the national debate on vaccines, as those who argue for individual rights have repeatedly come to a head with those who advocate for individuals’ communal responsibilities. In 2015, the California legislature decided to take a decisive stance on the issue in response to a measles outbreak at Disneyland, 14 years after measles had been declared eliminated from the U.S. by the Center for Disease Control (CDC). Senate Bill 277 eliminated any religious or personal vaccine exemptions, meaning that in order to attend any school, public or private, i n the state of California, one is required to be fully vaccinated, unless they have a legitimate medical condition that prevents them from being vaccinated.

Regarding the impacts of this policy on The Urban School of San Francisco, Charlotte Worsley, Assistant Head for Student Life, said, “the way the law reads, vaccination is verified at the 7th grade level.…Pretty much I’m just following the lead of the Department of Public Health. Because we’re not an elementary school, what they tell me is that [if someone was not vaccinated] it’s been caught. If someone is homeschooled, I may put a lot of attention there [to verifying whether or not they’ve been vaccinated].”

For Rhett Krawitt, a nine year old boy from Marin with leukemia, Bill 277 helped to ensure his ability to attend school. His father, Carl Krawitt, explained in an interview with the Urban Legend, “[Rhett] was finally becoming an operating member of society. He was going to school, he could go out in public… he could go to places where we knew that it was safe, because [we thought that] at school, kids had to be vaccinated…[but] what we learned over time was even if we asked, people had the freedom of personal choice to say ‘Hey, I don’t want to get vaccinated’ and we struggled with that.”

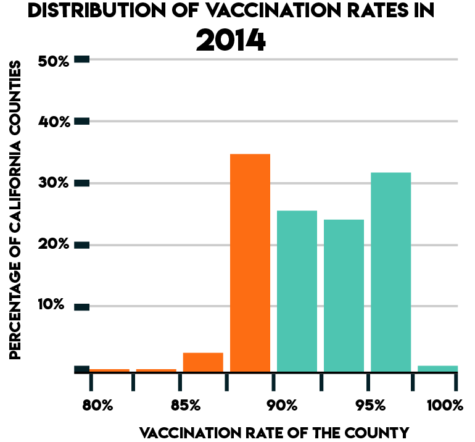

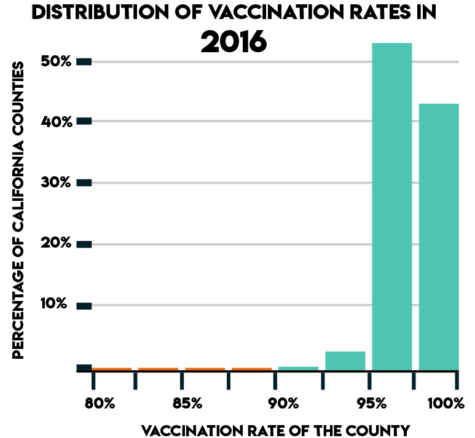

When an individual chooses not to vaccinate their child, they are not only putting their own child at risk of contracting that disease but they are directly endangering children like Rhett, whose compromised immune systems (from chemotherapy in his case) precludes them from getting vaccines. Students like Rhett rely on herd immunity: the concept that when enough members of a community are vaccinated, even if one person gets infected, it can’t spread very effectively and can get treated and dealt with before infecting immunocompromised members of the population. According to Oxford Department of Pediatrics, for some diseases, like measles, 90-95 percent of the population must be vaccinated “in order to effectively keep a population safe, to slow or stop the spread of the disease…. There are thousands of people with HIV and are immunocompromised and can’t get vaccinated. There are millions of babies under the age of one who aren’t quite ready to receive vaccines….so it’s important to get it up so high so there’s enough of a barrier that even if someone gets it, it doesn’t spread.”

Despite the advocacy work of doctors and families like the Krawitts, fear-mongering and misinformation is still pervasive. Urban School Infectious Disease teacher Mary Murphy explained that “you might have a family whose child has had a bad reaction to the vaccine, or has some other health condition that happens to arise at the same time that vaccination schedules are common and blames the vaccination. And there’s a lot of bad information around about that.”

However, in reality, vaccines are scientifically proven to be safe, and the CDC website reports, “Any medication can cause a severe allergic reaction. Such reactions from a vaccine are very rare, estimated at about 1 in a million doses, and would happen within a few minutes to a few hours after the vaccination.” Fear and confusion do lead to some parents’ decisions not to vaccinate their children.

As it is parents who make these decisions for all students under 18, it can be challenging to discuss vaccinations in a school setting. In most cases, students don’t have the autonomy to decide whether they want to get vaccinated and are often confused about their own vaccination histories. For example, one Urban student said, “I got everything late or with a lot of resistance, so it felt like I wasn’t getting everything. The one that I haven’t got is one of those two [hepatitis or HPV] and the way you get it is through having sex. So my mom [is] convinced that because doctors strongly recommend it by the age of 15 that everyone else in the community would have gotten the vaccine so there’s no way for me to get it.”

A junior**, who experiences similar confusion regarding her own vaccination history, said, “we had a family friend that…got a vaccine and then instantly got the sickness and became paralyzed from the waist down and my mom uses it as evidence constantly that I shouldn’t get any vaccines. I think they just freak her out.” As a result of the student’s mother’s hesitancy, the junior reports that she does not believe he/she has received the MMR or meningitis vaccine, possibly among others.

Senate Bill 277 did combat some of this doubt for families that were uncertain about the efficacy or safety of vaccines. “Thankfully, our law has passed and it worked. Instead of people saying, ‘oh, I’m not going to vaccinate my kid, I’m going to homeschool them,’ they’ve gone out and got their kids vaccinated,” said Carl Krawitt.

However, after the legislation passed, there was a sharp spike in medical exemptions, leading to some suspicion around how people were getting medical exemptions and if all of them were legitimate. According to the Marin County website in the 2016-2017 school year, “Marin saw a ten-fold increase in medical exemptions. This year the medical exemption rate is 2.1 percent, up from 0.2 percent in the 2015-16 school year.”

When asked whether she has observed an increase in medical exemptions at The Urban School, Worsley said, “I have no idea,” and that keeping statistics on exemptions “would be interesting, but it’s just not a high priority for me ….. No one here has time to do that. Our focus is just making sure we have the records and have students follow the law.”

There are certain tell-tale signs that people are getting medical exemptions for potentially illegitimate reasons. “What you’ll find is that the person who signs the medical exemption for the person for the anti-vaxxer is oftentimes not the family doctor. They only went to that doctor for purposes of getting the medical exemption for vaccination. But health officials aren’t looking at that stuff,” explained Carl Krawitt.

At Urban, this conversation features prominently in the Infectious Disease class, where there are often lively conversations about the importance of vaccines and how best to ensure their use. Murphy referenced a moment in a class she was teaching when a student revealed they were undervaccinated and the silence that followed.

“It was an interesting moment for me and a broader teaching point about how we talk about things when it’s not in the room versus when it’s in the room and how people change. I think people…can get really angry and really nasty but if they turn and it was the person sitting next to them who was not vaccinated, I think their tone would change. Is it really useful to be really angry and hateful about someone’s ignorance?” pondered Murphy.

** An earlier version of this story published the name of the junior. We have since redacted his/her name due to recent concerns being brought to our attention.