The event the world was supposed to “never forget” is forgotten from the Urban curriculum

Five years ago, Urban spent one week of History 9A studying the Holocaust. But, for the last several years, Urban students have not learned about the Holocaust or the history of antisemitism as a part of their history curriculum.

Five years ago, Urban spent one week of History 9A studying the Holocaust. But, for the last several years, Urban students have not learned about the Holocaust or the history of antisemitism as a part of their history curriculum.

Learning about the Holocaust is an educational requirement for California public schools between 7th and 12th grade. Despite this, many schools including Urban no longer teach about the Holocaust in required or elective history courses. A recent survey by Schoen Consulting, a data collection group, reported that 66% of American millennials didn’t know what Auschwitz was and 41% believed that two million or fewer Jews were killed in the Holocaust at the time of the survey.

The growing gap in education surrounding the Holocaust is perceived by some students as a failure of their schools to adequately teach about the impact of this historical event.

Julia Susser ‘22 has been in conversation with the administration about the possible addition of the Holocaust to the Urban curriculum. “I asked about [the Holocaust] in middle school and they said, you’ll learn it in high school,” said Susser. “I was like, okay great and I went to high school and I asked hey, why don’t we learn about it in high school? And they said some people learned [about] it in middle school.”

Rebecca Shapiro, chair of the Urban history department, explained that when she used to teach Night, by Ellie Weisel, a book about the Holocaust, 12 years ago in History 9A, “somewhere between one-quarter and one-half of the students had already read the book” which made the class feel repetitive for many students.

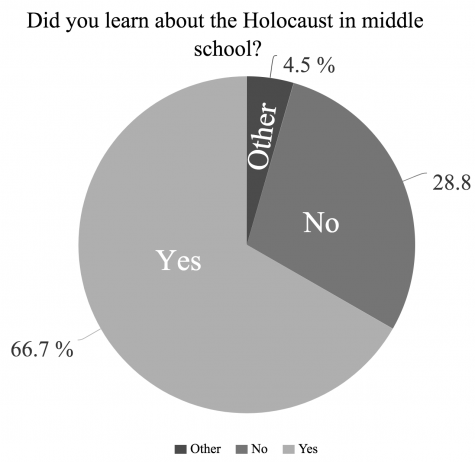

Though high schools may assume that students receive basic Holocaust education in middle school, not all students have learned about the Holocaust. According to a recent poll conducted by the Urban Legend, out of a random group of 66 students, 66.7% of Urban students recall learning about the Holocaust in middle school, 28.8% do not recall learning about the Holocaust, 4.5% learned about it in some context but felt it was too brief or insufficient, and 87.7% of students feel there is more to learn about the Holocaust and would like to learn more.

The decline in Holocaust education has also followed a dramatic rise in antisemitism in recent years. The Anti-Defamation League, a Jewish anti-hate organization, reported that the year 2019 had the highest level of antisemitic incidents since the organization began tracking antisemitic incidents in 1979, a 12 percent increase from 2018.

In an Atlantic Op-ed, Walter Reich, professor of international affairs, ethics, and human behavior at George Washington University and a former director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, wrote, “anti-Semitism has returned, in part, because the general public’s knowledge about the Holocaust—of what exactly it was, who exactly was murdered in it, how many were killed, and how anti-Semitism spawned it—has diminished.”

Co-leader of Urban’s Jew Crew, an affinity space for Jewish identifying students, Samuel Levine ‘21 believes that many middle schools are failing in their duty to teach about the Holocaust. “There’s sort of a persistent lack of knowledge [about the Holocaust] that I’ve seen which reflects a real failure of the middle school education system.”

Without sufficient background on the Holocaust, some Urban students also feel they cannot actively engage in discussions about the Israel-Palestine conflict, a topic that unlike the Holocaust, is covered for all Urban freshmen in English 1B. “In order to even have a fair and real debate about Israel-Palestine, students need to understand why Israel needs to exist in the first place,” said Susser. “And you can’t if you don’t understand how 6 million people died, and why [Israel] is perceived as the safe haven for Jews.”

However, Shapiro explains that the absence of the Holocaust in the Urban curriculum is less of a purposeful exclusion and more a reflection of the reality of limited curriculum space. “The challenge for any history department and any teacher is that there’s never enough time to discuss everything that we want to discuss and that we feel we need to discuss,” said Shapiro.

In an attempt to move away from a Eurocentric approach to history, the history department now focuses on teaching about the Armenian genocide in History 9A. For Shapiro, this decision also reflects the complexity of Jewish identity historically and currently. “For me being Jewish is a low-grade kind of challenge in operating in society, which I wouldn’t try to equate with being black or being indigenous or being queer. So I have a huge hesitancy in terms of where to locate [Jewish] history in our curriculum because it can go in so many different directions,” said Shapiro.

Susser though, questions the veracity of the anti-Euro-centric approach when used as a reason to not teach about the Holocaust. She explains that the Nazis killed queer people, Black people, and many other minority groups which could allow for a greater discussion beyond Jewish people and their history.

Some students have called for the Holocaust to be integrated into the required Urban curriculum as a part of a history or english class, even as an elective class. In an english class, Susser feels studying the Holocaust could open valuable discussions on human resilience and the complexity of humanity; “I think there are so many core parts of being human that are taught in the Holocaust,” she said.

Looking to where the Holocaust might fit into Urban’s history curriculum in the future Shapiro said, “[our revisions to the History curriculum] are driven by student interest and demand and curiosity.” She added, “I think if you came back in three years and looked at our curriculum, I wouldn’t be surprised if [the Holocuast] was there, and I’m not sure I’d be surprised if it weren’t.”