Religious dialogue necessary for inclusive community

Graphic made by Kian Nassre

For the first nine years of my education, I took three religion classes per week, had morning chapel every Friday and was exposed to Christian values. Suddenly, within three months of leaving that school, religion was no longer a part of my education. At first, I was too wrapped up in the excitement of freshman year to notice that religion was seldom mentioned at Urban. As a freshman, I thought this might be due to the fact that many of the students at Urban are non-religious, or that perhaps I just wasn’t looking in the right place. I soon came to realize, however, that religion was present on campus, but talked about minimally and often irrelevant.

My elementary school defied many of the assumptions often made about religious schools; we had a gay Latin teacher, we learned Darwin’s theory of evolution in science classes and we were taught not to interpret the bible word for word. However, when I arrived at Urban, where one of the core values is to “honor the uniqueness of each individual and embrace diverse backgrounds, values and points of view to build a strong, inclusive community,” I heard religious assumptions made in class and in the halls. One such assumption involves connecting one’s religious identity to their political beliefs. At Urban, a predominantly liberal school, I have often heard people link Christianity to the Republican Party. I am Christian and lean democrat, so it is troubling to hear these comments given Urban’s commitment to celebrating differences.

“Typically people see religion through politics as someone forcing their religion down someone else’s throat because of the idea of separation of state and how many conservatives and religious people believe it should not be separated,” said Latté Hutchinson (‘18), who practices Christianity and believes that in terms of politics, church and state should be separated.

While my religion does not dictate my political views, I still attempt to follow the main values of Christianity, which I believe to be grace, hope, love, faith, justice, joy, service, and peace in my everyday life.

“I have heard the occasional joke of people not taking prayers or blessings seriously, which is somewhat uncomfortable,” said Lizzy Hayashi (‘20), who regularly attends an Episcopal church and is a part of its youth group.

“I have heard people say, ‘I am going to temple this weekend’ with the response ‘oh, that’s cool,’ but when someone says ‘I have to go to church this weekend,’ people are like ‘why are you going?,’” said Kelsey Puknys (‘19). Puknys described the lack of spaces offered at Urban for religious people to convene. “There is Jew Crew, but there is not a place for people of other religions,” she said. Puknys was unsure whether she would actually attend a club or affinity group dedicated to a religion, but agreed that religion is often stigmatized at Urban. “People at Urban are very vocal about why they are not religious and kind of convey that maybe you shouldn’t believe in that either,” she said.

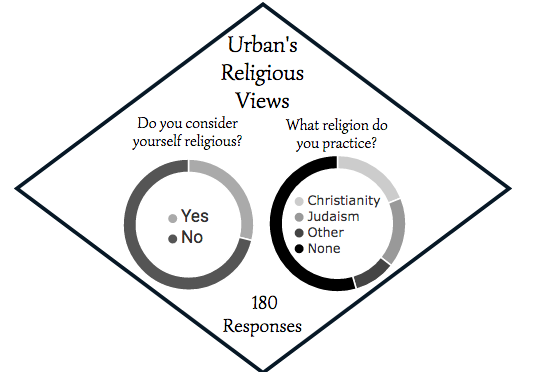

In a recent survey conducted by the Urban Legend, 28.9 percent of the 180 students surveyed considered themselves religious. The lack of religious students could be due to the fact that San Francisco is the second least religiously affiliated metro area in the United States, according to the American Values Atlas.

Although prospective students seeking a religious education may be more likely to look into Saint Ignatius College Preparatory, Convent of the Sacred Heart, Sacred Heart Cathedral Preparatory, Immaculate Conception or other religious affiliated high schools, it is extremely important that Urban creates a space for religious dialogue at Urban.

“Urban is a values-based institution … we want kids to be understanding and self-reflective, and I would say that those are all fundamental components of having any type of religious or spiritual practice. But we are not a religious institution, so we are not trying to educate people on various doctrines or theological beliefs that guide a religious experience,” said Clarke Weatherspoon, Dean of Equity and Inclusion and history teacher at The Urban School. Weatherspoon said that there is room to talk about religious experiences, but like most other affinity groups and clubs, further conversation would have to be driven by students. “We wouldn’t start a group for religious people if people didn’t want it,” said Weatherspoon.

As Weatherspoon mentioned, it is important to remember that Urban is not a religious institution. However, I often feel that religion at Urban is neglected in conversations about identity. The topic was brought up once in my Service Learning class and several years ago an event was held during the Multicultural Celebration about religion. However, considering that almost one third of students surveyed considered themselves religious, it strikes me that Urban rarely brings up the topic outside of those spaces. Affinity groups and clubs are run by students who are passionate about a particular topic or want a place to be with people of similar identities. If 28.9 percent of surveyed students claimed they were religious, then why is there no interest from students in creating a space available for religious dialogue?

Discussions about religion must not be stigmatized because these diverse beliefs will help lead Urban to a more diverse community. While it may not be necessary to create religious affinity groups or clubs, a conversation must be had about religion at Urban in the classroom, during forums possibly held during Multi Culti week, or at All School Meetings.