Midterm Madness Part II: What to Know

Will the House of Representatives flip on Nov. 6? Are Democrats doomed in the Senate? In Part II of Midterm Madness, I will explain the various political battlegrounds of 2018 from a macroscopic view. To do this, I will go into why the Democrats are not guaranteed to take the House from Republican control. I will also explain the complicated nature of the Senate elections this year and why so many key races are in hostile territory for Democrats. To cap it off, I will summarize where Democrats could make significant gains on the state level.

THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Democrats need to gain at least 23 seats to gain a majority in the House of Representatives (more if they lose some of their exposed seats in rural Minnesota). With polling of the entire nation suggesting a preference of Democrats by roughly nine percent, Democrats are favored to take the House, but there is a caveat: gerrymandering.

What is gerrymandering?

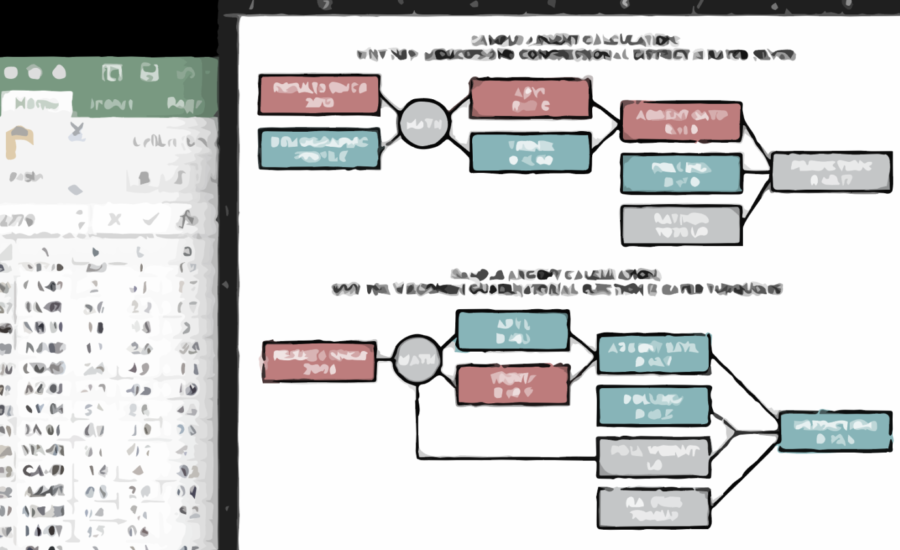

Every 10 years, after the census, congressional district lines are redrawn. This process is usually done by the state governments. After the colossal Republican gains in 2010, Republicans drew lines in dozens of states that packed Democrats into a few districts while cracking the rest between many, thus preventing them from winning majorities in most districts while ensuring they win vast majorities in a few. 2012 demonstrated the effectiveness of gerrymandering, when Democrats failed to regain the House despite winning more votes than Republicans.

While Democrats do gerrymander, they do it far less frequently and severely than the GOP. The most notable GOP gerrymanders are in Texas, Ohio, North Carolina and Michigan. These states all have one to three seats that Democrats only have a shot of picking up because the Democrats are so favored nationwide, plus at least three (Texas has eight) seats that are just out of Democrats’ reach, even in a blue wave. This is in addition to the already unfair seat distributions in those states (North Carolina is a swing state, but 10 out of its 13 districts are occupied by Republicans). Other states with significant GOP gerrymanders include Virginia, Wisconsin, Indiana, Georgia, Utah, South Carolina, Alabama and Louisiana. Several other GOP gerrymanders have been dampened by courts (Florida), rendered mute by the blue wave (New Jersey), or have not caused any significant seat imbalance (Oklahoma).

In 2016, Democrats lost the popular vote for House elections by one percent. In 2018, they are forecast to win it by roughly nine. For the record, a nine point popular vote victory is a lot, hence the 2018 has the moniker of “blue wave.” Theoretically, this 10 point swing would manifest as Democrats gaining 10 percent of the house (44 seats). While this could happen, the conversion rate between popular vote and seat wins is not linear. The implications for 2018 are that Democrats winning by only seven percent could cost them the House, while winning by 10 percent could give them 30 more seats than they need.

THE SENATE

Even though Democrats only need to gain two seats to take it, the Senate is a far more complicated political warzone due to the harsh conditions for Democrats. Senate seats are up for reelection every six years, and 2006 and 2012 were both very good years for Democrats. This has resulted in Democrats having to defend 26 out of 35 seats up this cycle, including 10 in states Trump won and five that he won by double digits. The news is not all bad for Democrats, however. While it is perhaps hard for us to imagine a Democrat winning in Montana, Missouri or West Virginia (yes, all of those seats are held by Democrats who won in 2012), red state Democrats tend to stray from the norms of the Democratic party in ways that appeal to their right-of-center constituents. Many of these incumbents have deep ties to their states or are relying on the fact that their states are far less red down ballot. Down ballot refers to the elections that receive less attention than the most important races, hence they are literally lower on the ballot. An example is how West Virginia, one of the reddest states in the country, regularly elects Democrats due to a phenomenon called ancestral democrats.

What are ancestral Democrats?

The trick to understanding the paradox of an ultra-red state with Democrats down ballot is to realize that the Democratic party in these states is very different from the national Democratic party. In West Virginia, a Democrat is not a city-dwelling liberal, but rather a blue-collar social conservative not quite divorced from a time when rural voters were Democrats and urban voters were Republicans. This phenomenon of conservatives who vote Democrat for non-presidential races is referred to as “ancestral Democrats,” and it often comes into play in Senate, gubernatorial, and state legislature races. The key to these Senators’ survival is a tightrope act of voting with the party when necessary, while also appealing to Trump supporters by not making any moves seen as opposing the President or his agenda, such as campaigning to protect Mueller or voting against Kavanaugh. This is why all of them opposed the Obamacare repeal and tax reform, yet three supported Neil Gorsuch last January and were forecast to vote for Kavanaugh until the sexual assault allegations by Christine Blasey-Ford. (One still did.)

What about the GOP?

On the other side of the aisle, Republicans are defending just nine Senate seats this year, and most of them should not be in play. Democrats only need to net two seats to win a majority, but that is a tough ask. If they do accomplish a miracle by keeping all 26 of their exposed seats, then they could win a majority through the Clinton-won state of Nevada and the trending-blue state of Arizona. Additionally, circumstances have made Republican-held Senate seats in Texas, Tennessee and a special election in Mississippi competitive.

THE STATES

Why do Democrats need to win big in state elections?

On the state level is a set of elections that receive less coverage than the House or Senate, yet are even more consequential for policy making. Many of the Democratic Party’s problems stem from its colossal losses on the state level in 2010 and 2014. Each state has its own House (usually called the state assembly) and a state senate, which has larger districts. A “trifecta”—also referred to as “unified control”—is when one party has a unified government, meaning that it controls the governor’s mansion, state assembly, and state senate. As of now, Democrats only have unified control of eight states (11 if you count blue states with liberal Republican governors), while Republicans have unified control of 26 (27 if you count North Carolina, which has a Democratic Governor whose powers have been stripped by the legislature). Although special elections since 2016 and the 2017 elections in Virginia and New Jersey have allowed Democrats to claw back some ground, they are in a deep hole and need to gain a lot of seats in 2018 and 2020 if they want to pass legislation or prevent another volley of gerrymandering.

Where are the governor mansions up for grabs?

On the gubernatorial level, term limits have left many seats won by Republicans in 2010 and 2014 open. Of the 25 seats the GOP is defending this cycle, 12 have no incumbent. The same is true for four out of the nine seats Democrats are defending this cycle. In sharp contrast to the Senate, Democrats have very few exposed seats to worry about while Republicans have plenty but are betting on incumbency to help them out. Among the list of Republican governorships up for grabs are the typical swing states of Ohio, Florida, Nevada, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, New Hampshire and Maine, most of which are critical for preventing another bout of gerrymandering and for influencing legislative policy. Also up for reelection are several Republicans in blue states. While some of these are obvious Democratic pickups, others are held by liberal Republicans who do not fit the mold of the national GOP and are heavily favored. Democrats also have some opportunities in several historically red states such as Arizona, Georgia, South Dakota, Kansas and Oklahoma.

What about the state legislatures?

Last is the least discussed element of any election: the state legislatures. The scale of Republican dominance in many swing states is so massive that Democrats can only get within striking distance of majorities so that they can take majorities in 2020. However, there are still many chambers that are within reach for Democrats. The State Senates in Colorado, New York, Maine, Wisconsin, Arizona and New Hampshire only require a small handful of seats to flip, and the volatility of the New Hampshire Assembly (seriously, read up on this; it is one of the strangest things in all of politics) has made it a possible pickup.

Read Part III of Midterm Madness to see what I think will happen in all these races.